Frederick Curson

PRIVATE Frederick Curson served in the 101st Company Labour Corps and previously in the 30th Battalion Royal Fusiliers. He died on 17th May, 1918 and is buried in St Sever Cemetery in Rouen.

Frederick was born in Hethersett on 3rd November, 1883 and baptised in St Remigius Church on 3rd February 1884. In the 1901 census he is shown as still in the village and living with his aunt and uncle William and Ellen Curson. By then he was 17 years of age and working as a bricklayer.

Frederick married Mary Elizabeth Burton on 16th August,1906. They had one daughter, Marjorie Hilary.

It is not clear how he came to be gassed on 13th May, 1918 but he was in No 9 General Hospital, Rouen, where he died on 17th May, 1918. The most likely cause of death would have been due to inhalation of mustard gas, the type most feared by the soldiers. Frederick had been in France for about two years. It is known that he was home on leave just before Christmas 1917.

It would appear that Frederick was employed by the Labour Corps at the time of being gassed, having previously been in the 30th Battalion Royal Fusiliers. He would have been employed in vital if unglamorous work digging trenches, moving stores, repairing roads and railways etc. The Labour Corps had been formed in 1917 and contained men who had been previously wounded and were unable to return to fighting duties, as well as those who, upon enlistment, were found to be medically unfit or conscientious objectors who would serve in the military, but no fight. Labour Corps soldiers were not immune from snipers, artillery fire, aerial attack, disease or indeed gas attack, and the corps suffered some 9,000 deaths during the last two year of the war.

A memorial service was held for Frederick Curson in St Remigius on June 2nd, 1918.

Chris Thrower has sent the following additional details on Frederick -

Frederick was Wicket Keeper for the Hethersett Cricket team which won the Norfolk Junior Cup in 1906 beating YMCA, the favourites by 64 runs. The village was jubilant “You’d have thought we had beaten Australia” said Fred Dodman, the Captain.

Frederick’s death was as a result of one of the most serious incidents involving a Labour Corps Company on the Somme.

This most devastating attack occurred on the night of 11/12th May, 1918. On that night 101 Company was burying cables at Fonquevillers when the area was attacked with both high explosive and gas shells from 7.30 p.m. until 2.30 a.m. Initial reports suggested that no men were killed during the attack although IV Corps Diary refers to 40 Officers and possibly 1,400 men being gassed. Frederick was taken to the No 9 General Hospital in Rouen, where he died on 17th May, 1918. The most likely cause of death would have been due to inhalation of mustard gas, the type most feared by the soldiers.

Frederick was born in Hethersett on 3rd November, 1883 and baptised in St Remigius Church on 3rd February 1884. In the 1901 census he is shown as still in the village and living with his aunt and uncle William and Ellen Curson. By then he was 17 years of age and working as a bricklayer.

Frederick married Mary Elizabeth Burton on 16th August,1906. They had one daughter, Marjorie Hilary.

It is not clear how he came to be gassed on 13th May, 1918 but he was in No 9 General Hospital, Rouen, where he died on 17th May, 1918. The most likely cause of death would have been due to inhalation of mustard gas, the type most feared by the soldiers. Frederick had been in France for about two years. It is known that he was home on leave just before Christmas 1917.

It would appear that Frederick was employed by the Labour Corps at the time of being gassed, having previously been in the 30th Battalion Royal Fusiliers. He would have been employed in vital if unglamorous work digging trenches, moving stores, repairing roads and railways etc. The Labour Corps had been formed in 1917 and contained men who had been previously wounded and were unable to return to fighting duties, as well as those who, upon enlistment, were found to be medically unfit or conscientious objectors who would serve in the military, but no fight. Labour Corps soldiers were not immune from snipers, artillery fire, aerial attack, disease or indeed gas attack, and the corps suffered some 9,000 deaths during the last two year of the war.

A memorial service was held for Frederick Curson in St Remigius on June 2nd, 1918.

Chris Thrower has sent the following additional details on Frederick -

Frederick was Wicket Keeper for the Hethersett Cricket team which won the Norfolk Junior Cup in 1906 beating YMCA, the favourites by 64 runs. The village was jubilant “You’d have thought we had beaten Australia” said Fred Dodman, the Captain.

Frederick’s death was as a result of one of the most serious incidents involving a Labour Corps Company on the Somme.

This most devastating attack occurred on the night of 11/12th May, 1918. On that night 101 Company was burying cables at Fonquevillers when the area was attacked with both high explosive and gas shells from 7.30 p.m. until 2.30 a.m. Initial reports suggested that no men were killed during the attack although IV Corps Diary refers to 40 Officers and possibly 1,400 men being gassed. Frederick was taken to the No 9 General Hospital in Rouen, where he died on 17th May, 1918. The most likely cause of death would have been due to inhalation of mustard gas, the type most feared by the soldiers.

The hospital, one of several, was on the south side of the city of Rouen at the Race Course, the St Sever Cemetery and Extension, which contains 8,500 Great War casualties, is opposite this site.

Most of the men killed in this attack are buried here.

Within five days of the gas attack the remnants of 101 Company were employed on roadwork at Orville and on 18 May received 200 replacements. It is not known how many of the remaining 150 other ranks may have later died as a result of the gassing.

Frederick had been in France for about two years. It is known that he was home on leave just before Christmas 1917.

Frederick was employed by the Labour Corps at the time of being gassed, having previously been in the 30th Battalion Royal Fusiliers. He would have been employed in vital if unglamorous work digging trenches, moving stores, repairing roads and railways etc. The Labour Corps had been formed in 1917 and contained men who had been previously wounded and were unable to return to fighting duties, as well as those who, upon enlistment, were found to be medically unfit to fight. Labour Corps soldiers were not immune from snipers, artillery fire, aerial attack, disease or indeed gas attack, and the corps suffered some 9,000 deaths during the last two year of the war.

A memorial service was held for Frederick Curson in St Remigius on June 2nd, 1918. His widow and daughter were unaware that he had a grave in France. His remaining family have been able to visit Frederick’s grave on several occasions since the discovery of its location.

Most of the men killed in this attack are buried here.

Within five days of the gas attack the remnants of 101 Company were employed on roadwork at Orville and on 18 May received 200 replacements. It is not known how many of the remaining 150 other ranks may have later died as a result of the gassing.

Frederick had been in France for about two years. It is known that he was home on leave just before Christmas 1917.

Frederick was employed by the Labour Corps at the time of being gassed, having previously been in the 30th Battalion Royal Fusiliers. He would have been employed in vital if unglamorous work digging trenches, moving stores, repairing roads and railways etc. The Labour Corps had been formed in 1917 and contained men who had been previously wounded and were unable to return to fighting duties, as well as those who, upon enlistment, were found to be medically unfit to fight. Labour Corps soldiers were not immune from snipers, artillery fire, aerial attack, disease or indeed gas attack, and the corps suffered some 9,000 deaths during the last two year of the war.

A memorial service was held for Frederick Curson in St Remigius on June 2nd, 1918. His widow and daughter were unaware that he had a grave in France. His remaining family have been able to visit Frederick’s grave on several occasions since the discovery of its location.

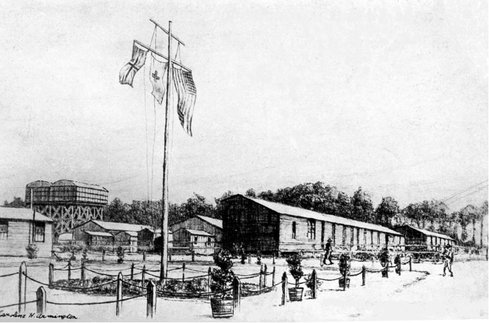

Drawing of General Hospital No 9, May 1917.

Drawing of General Hospital No 9, May 1917.

More About the Rouen Hospitals

General Hospitals 5, 6, 9 and 12 were located at the Race Course, Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray in the southern outskirts of Rouen. General Hospital N°9 was run by Base Hospital N°4 from May, 1917 to March 1919.

Base Hospital No. 4 was organized at Lakeside Hospital, Cleveland, Ohio, USA, during August, 1916, and was mobilised at Cleveland about May 5, 1917. The unit left Cleveland on May 6, 1917, arrived at New York and embarked on the Orduna May 7, 1917. It sailed for Europe on May 8, 1917, arriving at Liverpool May 17, thus being the first unit of the United States Army to reach Europe. After spending several days in London, it left there on May 24, en route to Rouen, France, arriving at that station for duty on May 25, 1917. It was one of the original six base hospitals sent to Europe for duty with the British and remained with the British Expeditionary Force in France during its entire overseas existence, operating as No. 9 General Hospital, British Expeditionary Force. It ceased functioning about March 1, 1919, sailed from Europe on the Agamemnon on March 31, arrived in the United States on April 7, 1919, and was demobilised shortly thereafter. "... I visited our station, General Hospital N°9, B.E.F. which was, they told me, one of the best hospital in France. It had 1,540 beds, 1,240 regularly, with a crisis expansion of 300.

...At N°9 we cut down a great pine from the beautiful forest of Rouen and, for the first time officially raised Old Glory in Européan war, flying her beside the Union Jack and the Red Cross flag.

The next day, May twenty-eight [1917], we began to take over the service. At last we were in the war."

Crile G. An Autobiography. New York: Lippincott Company,1947 (1):279-80.

Rouen was the centre of the southern line of British hospitals in France. Fourteen base hospitals in the vicinity, among them B.E.F. No. 12, served as receiving stations for the wounded mainly from the area of the Somme. After treatment at one of these base hospitals, the British wounded were evacuated down the Seine to England; the French, and later American wounded, were sent to Southern France. B.E.F. General No. 12, to which the St. Louis unit had been assigned, was one of the earliest British hospitals established in France. It had been situated on the racetrack, the Champs des Courses, at Rouen since August 1914, with the exception of one brief period during that first year when an advancing German army forced it to flee down the Seine River. The sandy, gravel-covered ground of the racetrack provided the best drainage in Rouen for a 1,300-bed hospital built in the midst of the rain belt of the Seine Valley. Even the locals described the town as the “pot de chambre de France.”

As the doctors and enlisted men from St. Louis looked about that June 12 morning they saw only an establishment of moss covered bell tents illuminated by comic candle lanterns. Only two huts of about 30 beds each and a small ward of 10 beds attached to the operating room accommodated patients not under canvas. These facilities would prove to be marvelous in spring and summer. However, the one stove in each tent hardly provided sufficient heat to keep the patients, doctors or nurses warm in winter. The water inside the tents froze every winter night despite the fire in the stoves. Often the day nurse’s first duty in the morning was to thaw the solutions and medicines in the bottles before she could administer them.

The permanent buildings of the racetrack, such as the pavilions, paddocks and cafe, had been put to use, but for administrative purposes rather than patient care. The hospital office was located in the racetrack office, the laboratory in the Post de Police, the office of the commanding officer in a Vestarie under a pavilion and the officers’ mess in the Salon. The medical officers had established quarters outside the pavilions in small bell tents, similar to those used for the wounded. The racing turf remained free of buildings until later in the war. With a surrounding line of trees, it gave a picturesque appearance to the hospital and served as an excellent ground for tennis, cricket and other ball games, as well as drills and parades. Grass covered the ground between the tents and flowers bloomed here and there. The British attempted to make the surroundings in all military hospitals as pleasant and attractive as possible. Thoughtfully given special attention, the nurses were ensconced in wooden huts located inside the protective barrier of the paddock fence.

General Hospitals 5, 6, 9 and 12 were located at the Race Course, Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray in the southern outskirts of Rouen. General Hospital N°9 was run by Base Hospital N°4 from May, 1917 to March 1919.

Base Hospital No. 4 was organized at Lakeside Hospital, Cleveland, Ohio, USA, during August, 1916, and was mobilised at Cleveland about May 5, 1917. The unit left Cleveland on May 6, 1917, arrived at New York and embarked on the Orduna May 7, 1917. It sailed for Europe on May 8, 1917, arriving at Liverpool May 17, thus being the first unit of the United States Army to reach Europe. After spending several days in London, it left there on May 24, en route to Rouen, France, arriving at that station for duty on May 25, 1917. It was one of the original six base hospitals sent to Europe for duty with the British and remained with the British Expeditionary Force in France during its entire overseas existence, operating as No. 9 General Hospital, British Expeditionary Force. It ceased functioning about March 1, 1919, sailed from Europe on the Agamemnon on March 31, arrived in the United States on April 7, 1919, and was demobilised shortly thereafter. "... I visited our station, General Hospital N°9, B.E.F. which was, they told me, one of the best hospital in France. It had 1,540 beds, 1,240 regularly, with a crisis expansion of 300.

...At N°9 we cut down a great pine from the beautiful forest of Rouen and, for the first time officially raised Old Glory in Européan war, flying her beside the Union Jack and the Red Cross flag.

The next day, May twenty-eight [1917], we began to take over the service. At last we were in the war."

Crile G. An Autobiography. New York: Lippincott Company,1947 (1):279-80.

Rouen was the centre of the southern line of British hospitals in France. Fourteen base hospitals in the vicinity, among them B.E.F. No. 12, served as receiving stations for the wounded mainly from the area of the Somme. After treatment at one of these base hospitals, the British wounded were evacuated down the Seine to England; the French, and later American wounded, were sent to Southern France. B.E.F. General No. 12, to which the St. Louis unit had been assigned, was one of the earliest British hospitals established in France. It had been situated on the racetrack, the Champs des Courses, at Rouen since August 1914, with the exception of one brief period during that first year when an advancing German army forced it to flee down the Seine River. The sandy, gravel-covered ground of the racetrack provided the best drainage in Rouen for a 1,300-bed hospital built in the midst of the rain belt of the Seine Valley. Even the locals described the town as the “pot de chambre de France.”

As the doctors and enlisted men from St. Louis looked about that June 12 morning they saw only an establishment of moss covered bell tents illuminated by comic candle lanterns. Only two huts of about 30 beds each and a small ward of 10 beds attached to the operating room accommodated patients not under canvas. These facilities would prove to be marvelous in spring and summer. However, the one stove in each tent hardly provided sufficient heat to keep the patients, doctors or nurses warm in winter. The water inside the tents froze every winter night despite the fire in the stoves. Often the day nurse’s first duty in the morning was to thaw the solutions and medicines in the bottles before she could administer them.

The permanent buildings of the racetrack, such as the pavilions, paddocks and cafe, had been put to use, but for administrative purposes rather than patient care. The hospital office was located in the racetrack office, the laboratory in the Post de Police, the office of the commanding officer in a Vestarie under a pavilion and the officers’ mess in the Salon. The medical officers had established quarters outside the pavilions in small bell tents, similar to those used for the wounded. The racing turf remained free of buildings until later in the war. With a surrounding line of trees, it gave a picturesque appearance to the hospital and served as an excellent ground for tennis, cricket and other ball games, as well as drills and parades. Grass covered the ground between the tents and flowers bloomed here and there. The British attempted to make the surroundings in all military hospitals as pleasant and attractive as possible. Thoughtfully given special attention, the nurses were ensconced in wooden huts located inside the protective barrier of the paddock fence.