Hethersett 1910 to 1920 - The First World War

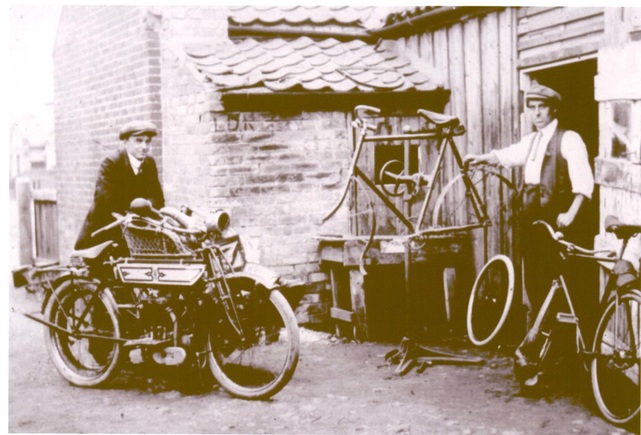

Just before the First World War a cycle shop was owned by Harry Childs and other members of the family ran this afterwards. Cycles were sold and repaired there. It later became Crossways Store and then the Post Office took it over and used it as a sorting office.

Harry Childs is standing in the doorway and Herbert Bailey is also pictured. This was the back of the shop and the photo was taken soon after the building was constructed.

Harry Childs was killed in the war and the ownership passed on. Harry's Father, William J, who was known locally as Childs the Snob, used the rear of the shop for boot and shoe making. When the floorboards were eventually lifted the under floor was covered with discarded shoe nails that had fallen through the boards. The building has subsequently been demolished.

In 1910 Hethersett was a much quieter place than our village of today. There were very few cars about and the delivery of goods was carried out on a horse drawn van or pony and cart. The number of residents was approximately one-sixth of what it is today.

Shopkeeping was vastly different with nothing prepared. Flour, sugar, rice and other commodities were delivered in large sacks and had to be emptied into drawers under the counter. Tea came in large chests and had to be weighed on demand, with customers ordering as little as two ounces. Very few people had more than 10s (50p) a week at their disposal and this had to be spent very carefully, with rent costing as much as 2s 6d or one quarter of the income. Sugar cost 2d a pound and flour 1 shilling a stone. Many households baked their own bread - usually on a Friday. Ovens were mounted on walls.

All dried fruit at the shops had to be cleaned through a large sieve and biscuits were a luxury, and none of them were packed. Malt was ground for home-brewed beer and tobacco cost up to 4d an ounce. Children had about 1d a week to spend. Shopping hours were long, starting at about 8 a.m and not finishing until between 7 and 10 p.m.

War with Germany was declared on 4th August, 1914. Hethersett was affected in the same way as every other Norfolk parish. Regular troops originating from the village had already been mobilised, reservists and territorials called up and eager volunteers, motivated by a mixture of patriotism, outrage, peer pressure and sheer adventure, had started to make their way to hastily arranged recruiting offices.

There was, at the time, a Hethersett detachment of F Company of the 4th Battalion Norfolk Regiment (Territorials) and in February, 1915, a Voluntary Force (an early form of Dad's Army) was started, using the Old School for drill practice on Monday and Thursday evenings at 8 p.m. It is likely that the Territorials also used this for their meetings, parade drills, lectures on guns and other things.

It is thought that at least six of the Hethersett men destined to lose their lives in the war would have been Territorials and so it is assumed that some of them would have known each other.

Conscription was introduced in early 1916. At first only single men were called up, but by the end of the war, as a result of the unforeseen catastrophic losses, even married men of 50 were required to serve.

Many Hethersett men served within the battalions of the Norfolk Regiment, but later in the war, as a result of the vagaries of army administration and the need to replace the mounting losses, many of the men found themselves in military units that to the casual observer seem to make no sense. The village Parish Magazine of 1916 list 115 local men serving of which 35 were in the Norfolks and the remaining 80 in over 30 other army or navy units.

Whilst the war was raging, the people of Hethersett were left to carry on with normal everyday life as best they could. Most residents had rarely travelled outside the village and the names of places reported in newspapers and described by men home on leave could have been from a different planet. Leisure trips abroad at the time had been purely and simply for the rich.

Life in Hethersett went on despite concern for sons, brothers and husbands serving on the Front. At home there were local celebrations for births and weddings, sad farewells as both childhood illness and old age took away both the young and elderly with scant regard for age.

Food was scarce as the price of bread rose. Pensioners struggled to make ends meet on five shillings per week and poaching was on the increase. The Food Ministry was urging people to eat less bread and a League of Voluntary Rationers and a Food Production Society were formed in the village in 1917 and on 12th May, 1918, special prayers were said for the coming harvest as nationwide rationing loomed.

Many people in Hethersett were fortunate to have gardens big enough to grow their own vegetables and some would have kept a few hens as well. Food hoarding was punishable by heavy fines and the shame of discovery.

There were constant appeals for monies for various good causes: flag days, house-to-house collections and concerts were held to raise cash and entertain local people who had no radios, televisions or other hi-tech amusements that we take for granted today. The occasional slide show (lantern lecture) was given and often consisted of a depiction of missionary work in Africa.

There were also weekly Tuesday working parties when scarves, mittens and socks were knitted for the soldiers and parcels were sent out to the Front containing cigarettes, pencils, paper and envelopes. At Christmas 1917, 110 parcels were posted to Hethersett servicemen and prisoners of war.

Many activities such as cricket, choir outings and Sunday School treats were abandoned for the duration of the war, but jumble sales and sales of work continued to help fill leisure time.

The wartime sporting theme , or lack of it, was taken up by A.J.R. Harris in his History of Hethersett Cricket Club "Merely Cricket."

"Yet all we can record of that season of 1914 is that "some of the matches were never played," and that the one played against YMCA on the 1st August was the last played by Hethersett (as with many another village club in effect) for several years. For three days later, war was declared. Within four months, nearly 50 of Hethersett's young men were already serving in the Forces. And that figure would be increased by more than half within a few more months. Cricket became merely a subject to dream and talk about, as some relief from pressing employments of a far less rational nature.

But the tradition and its spirit survived. So much so that when early in the Spring of 1919, the parish of Hethersett set about the task of "getting back to normal" the revival of cricket was regarded as being some minor contribution to that process."

Roy Jackson contacted the Hethersett Village web site with a number of reminiscences of his family which included mention of the First World War and the birth of his father in the very month that war broke out.

"My father, Edward Horace Jackson, was born in Hethersett in August 1914. He was son of the Blacksmith at the Smithy in Norwich Road, Horace Arthur Jackson, who had also been born in Hethersett in December 1886 son of John Jackson and Ellen. John Jackson was, as far as I can make out, a Coachbuilder and also had sons William (c1891), John (c1885), Alfred (who died in the First World War) and daughters Nellie, Edith (c 1882) and May (c 1890).

The iron bands around Kett's Oak, which we always used to see as we passed on the old A11, driving to visit my grandparents when I was a child, were replaced by my grandfather (HAJ) before he left Hethersett to live in Norwich. During the First World War he served as a blacksmith with the army in France and survived to return.

John Jackson (father of HAJ) also had a brother in Hethersett, Robert Jackson, known as "Bobbo". He was born about 1863 and became a general labourer. All we know about their parents is that the mother was called Sarah."

Shopkeeping was vastly different with nothing prepared. Flour, sugar, rice and other commodities were delivered in large sacks and had to be emptied into drawers under the counter. Tea came in large chests and had to be weighed on demand, with customers ordering as little as two ounces. Very few people had more than 10s (50p) a week at their disposal and this had to be spent very carefully, with rent costing as much as 2s 6d or one quarter of the income. Sugar cost 2d a pound and flour 1 shilling a stone. Many households baked their own bread - usually on a Friday. Ovens were mounted on walls.

All dried fruit at the shops had to be cleaned through a large sieve and biscuits were a luxury, and none of them were packed. Malt was ground for home-brewed beer and tobacco cost up to 4d an ounce. Children had about 1d a week to spend. Shopping hours were long, starting at about 8 a.m and not finishing until between 7 and 10 p.m.

War with Germany was declared on 4th August, 1914. Hethersett was affected in the same way as every other Norfolk parish. Regular troops originating from the village had already been mobilised, reservists and territorials called up and eager volunteers, motivated by a mixture of patriotism, outrage, peer pressure and sheer adventure, had started to make their way to hastily arranged recruiting offices.

There was, at the time, a Hethersett detachment of F Company of the 4th Battalion Norfolk Regiment (Territorials) and in February, 1915, a Voluntary Force (an early form of Dad's Army) was started, using the Old School for drill practice on Monday and Thursday evenings at 8 p.m. It is likely that the Territorials also used this for their meetings, parade drills, lectures on guns and other things.

It is thought that at least six of the Hethersett men destined to lose their lives in the war would have been Territorials and so it is assumed that some of them would have known each other.

Conscription was introduced in early 1916. At first only single men were called up, but by the end of the war, as a result of the unforeseen catastrophic losses, even married men of 50 were required to serve.

Many Hethersett men served within the battalions of the Norfolk Regiment, but later in the war, as a result of the vagaries of army administration and the need to replace the mounting losses, many of the men found themselves in military units that to the casual observer seem to make no sense. The village Parish Magazine of 1916 list 115 local men serving of which 35 were in the Norfolks and the remaining 80 in over 30 other army or navy units.

Whilst the war was raging, the people of Hethersett were left to carry on with normal everyday life as best they could. Most residents had rarely travelled outside the village and the names of places reported in newspapers and described by men home on leave could have been from a different planet. Leisure trips abroad at the time had been purely and simply for the rich.

Life in Hethersett went on despite concern for sons, brothers and husbands serving on the Front. At home there were local celebrations for births and weddings, sad farewells as both childhood illness and old age took away both the young and elderly with scant regard for age.

Food was scarce as the price of bread rose. Pensioners struggled to make ends meet on five shillings per week and poaching was on the increase. The Food Ministry was urging people to eat less bread and a League of Voluntary Rationers and a Food Production Society were formed in the village in 1917 and on 12th May, 1918, special prayers were said for the coming harvest as nationwide rationing loomed.

Many people in Hethersett were fortunate to have gardens big enough to grow their own vegetables and some would have kept a few hens as well. Food hoarding was punishable by heavy fines and the shame of discovery.

There were constant appeals for monies for various good causes: flag days, house-to-house collections and concerts were held to raise cash and entertain local people who had no radios, televisions or other hi-tech amusements that we take for granted today. The occasional slide show (lantern lecture) was given and often consisted of a depiction of missionary work in Africa.

There were also weekly Tuesday working parties when scarves, mittens and socks were knitted for the soldiers and parcels were sent out to the Front containing cigarettes, pencils, paper and envelopes. At Christmas 1917, 110 parcels were posted to Hethersett servicemen and prisoners of war.

Many activities such as cricket, choir outings and Sunday School treats were abandoned for the duration of the war, but jumble sales and sales of work continued to help fill leisure time.

The wartime sporting theme , or lack of it, was taken up by A.J.R. Harris in his History of Hethersett Cricket Club "Merely Cricket."

"Yet all we can record of that season of 1914 is that "some of the matches were never played," and that the one played against YMCA on the 1st August was the last played by Hethersett (as with many another village club in effect) for several years. For three days later, war was declared. Within four months, nearly 50 of Hethersett's young men were already serving in the Forces. And that figure would be increased by more than half within a few more months. Cricket became merely a subject to dream and talk about, as some relief from pressing employments of a far less rational nature.

But the tradition and its spirit survived. So much so that when early in the Spring of 1919, the parish of Hethersett set about the task of "getting back to normal" the revival of cricket was regarded as being some minor contribution to that process."

Roy Jackson contacted the Hethersett Village web site with a number of reminiscences of his family which included mention of the First World War and the birth of his father in the very month that war broke out.

"My father, Edward Horace Jackson, was born in Hethersett in August 1914. He was son of the Blacksmith at the Smithy in Norwich Road, Horace Arthur Jackson, who had also been born in Hethersett in December 1886 son of John Jackson and Ellen. John Jackson was, as far as I can make out, a Coachbuilder and also had sons William (c1891), John (c1885), Alfred (who died in the First World War) and daughters Nellie, Edith (c 1882) and May (c 1890).

The iron bands around Kett's Oak, which we always used to see as we passed on the old A11, driving to visit my grandparents when I was a child, were replaced by my grandfather (HAJ) before he left Hethersett to live in Norwich. During the First World War he served as a blacksmith with the army in France and survived to return.

John Jackson (father of HAJ) also had a brother in Hethersett, Robert Jackson, known as "Bobbo". He was born about 1863 and became a general labourer. All we know about their parents is that the mother was called Sarah."

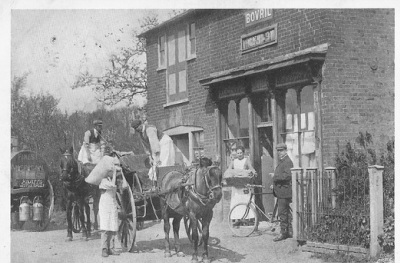

Donald Bailey sent us a copy of a postcard which gives a taste of how the village looked just prior to the First World War. It depicts a number of well known village landmarks and then depicts his great grandfather William Bailey and his wife Harriet (nee Skilling) and brother-in-law William Kent. They ran the general store in the village in the late 19th century and early 20th Century. The photo below depicts Baileys Stores on Great Melton Road around 1910. This is now Stratfords' Estate Agents next to Oak Square.

During the war, Hethersett had a War Savings Association which promised good investment with investors also helping the war effort. The association was formed in July, 1916, for the purposes of helping people who wanted to buy War Saving Certificates but could only make small contributions as the parish magazine explained:

The main advantage of investing your money through the Association will be that you get your money back with the interest that has accrued quicker than you would do if you invested through the Post Office.

A certificate cost 15s 6d (78p) and would bring a £1 return in five years.

There is no more profitable investment you can make. Your money is absolutely safe and, if at any time you need it, you can withdraw it plus whatever interest has accrued. If you can only save a few pence a week you cannot do better than join the War Savings Association.

The scheme also had great benefits for groups of people working and saving together as the issue of certificates would be back dated. In this way 31 people investing 6d (just under 3p) a week would lead to the issue of one certificate each week for 31 weeks. Thus the first certificate would be dated 31 weeks before any certificate bought by an individual who would have to invest for 31 weeks before getting a certificate. By the group method the interest implications would start immediately. The parish magazine continued:

The country is in great need of every penny you can lend to it if this war is to be finished off as we all want and intend to see it finished. It is costing more than six million pounds every day..... this sum must be found in the country by saving it and lending it to the nation..... There are not many who could not save a few pence every week, even the children could do it, by giving up sweets..... Think of what the men in the Trenches have given up? Are you helping to bear the burden? The country has asked them to do their part, and how splendidly and nobly and unselfishly they have responded everybody knows. The country now asks you to do yours.

During the war, Hethersett had a War Savings Association which promised good investment with investors also helping the war effort. The association was formed in July, 1916, for the purposes of helping people who wanted to buy War Saving Certificates but could only make small contributions as the parish magazine explained:

The main advantage of investing your money through the Association will be that you get your money back with the interest that has accrued quicker than you would do if you invested through the Post Office.

A certificate cost 15s 6d (78p) and would bring a £1 return in five years.

There is no more profitable investment you can make. Your money is absolutely safe and, if at any time you need it, you can withdraw it plus whatever interest has accrued. If you can only save a few pence a week you cannot do better than join the War Savings Association.

The scheme also had great benefits for groups of people working and saving together as the issue of certificates would be back dated. In this way 31 people investing 6d (just under 3p) a week would lead to the issue of one certificate each week for 31 weeks. Thus the first certificate would be dated 31 weeks before any certificate bought by an individual who would have to invest for 31 weeks before getting a certificate. By the group method the interest implications would start immediately. The parish magazine continued:

The country is in great need of every penny you can lend to it if this war is to be finished off as we all want and intend to see it finished. It is costing more than six million pounds every day..... this sum must be found in the country by saving it and lending it to the nation..... There are not many who could not save a few pence every week, even the children could do it, by giving up sweets..... Think of what the men in the Trenches have given up? Are you helping to bear the burden? The country has asked them to do their part, and how splendidly and nobly and unselfishly they have responded everybody knows. The country now asks you to do yours.

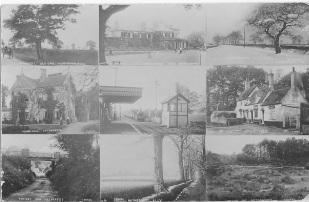

On the left are some images of parts of Hethersett taken around 1910

We have a flavour of what Hethersett was like in 1920 from the writings of resident Florence Eagle who, in 1924, had the following description:

"I well remember arriving in Hethersett on a sunny October day in 1924. Hethersett with a population at that time of about 1,100 seemed somewhere rather special. I decided that I must find out as much as possible about the village so that I could write in full detail to the friends I had left behind. My brother and I set off to explore the village. At that time there were two schools, three general stores, two butchers, plus two pork butchers; one of the latter was mainly a wholesaler. The Post Office was also a newsagents, tobacconist and ironmonger; at the shop opposite a variety of goods were sold including bicycles and boots and shoes. Repairs to these three items were carried out. On the site of the present supermarket stood an old army hut, where a motor and cycle repair business was carried out. Nearby stood a railway carriage which was the home and workshop of a tailor. Other businesses were builders, and an artesian-well engineer, a blacksmith and there were four public houses. The doctor's surgery was at Hethersett House.

I remember being impressed by the number of people in the church choir, including several middle-aged men. At that time the Methodist Church had a good male voice choir.

My visits to Norwich had been few and far between. I was pleased to find that buses ran to Norwich from Hethersett even though they were from the main road. There were no petrol pumps in the village. My father bought a motor vehicle before moving to Hethersett and he purchased his petrol in cans from the Post Office.

In 1924, quite a number of people were employed in the village. Apart from the businesses already mentioned there were farms, market gardens, an agricultural engineer, two coal merchants, a corn merchant, a saddler and at least 17 houses employed gardeners and indoor staff, some employed chauffeurs.

Quite a lot of laundry work was carried out in the village for people outside Hethersett. I think it was mainly for residents in the Newmarket Road, Norwich area. Hethersett had neither gas nor electricity. Gas came first in approximately 1925; when electricity came about a year later several people had their gas fittings removed and changed to electricity.

The roads were quite rough in those days, however, as it was before the car age many people enjoyed their Sunday afternoon walk; a popular round was Great Melton Road, New Road, the Main Road and Queen's Road, at that time there were no houses along New Road after turning left at Mill Road corner towards the main road.

Quite a number of houses in Lynch Green, Great Melton Road and some in Queen's Road were way back with a meadow or long garden in front of the house; several of these frontages have now been built on.

Ella Barnes (nee Ireland) was born in Hethersett in 1911 and wrote about a walk around Hethersett in the 1920s when there was plenty of open space and fields:

There was no electricity, gas or piped water. Water was obtained from wells and pumps and the roads were untarred:

"Walking down Great Melton Road from Lynch Green, apart from dwellings occupied by Mr and Mrs Mapes and one by Mr Levine, there was no other development on the right nearly down to the junction with Henstead Road. On the left were the dovecoats, next to two little cottages .... Then there were two small cottages on the other side of the road. Further along was the chapel and next it it a grocer's shop run by a Mr and Mrs Kent. In Oak Square was a bakery run by two Mr Smiths, while next was a butchers, William Curson. Then came two more little houses. Mr and Mrs Pike lived in one, and he was a gents' hairdresser (called a barber), while in the other lived PC Burton and his family. There was nothing further on this side until the Post Office on the corner (now the McMillan Charity Shop) run by Miss Buckingham and her son. Almost opposite in Great Melton Road was a long driveway to a house and alongside was the old bicycle shop which also sold paint, wallpaper and a few clothes, and this was run for years by the Childs' family until it is thought the lease ran out. The big house next to this and down another driveway included a pork butcher run by Ernest Smith.

On the right, further down the road, was a grocer's shop run by Mr and Mrs Sharman. Just past the grocers was a house standing back from the road. There was nothing more until Cann's Lane. On the other side of the road there were no buildings until you reached Beech Grove Farmhouse. On the corner of Cann's Lane was Beech Cottage. There was nothing on either side until you reached a row of cottages next to the then Village Hall and what is now Hethersett Social Club. Then followed a grocer's shop followed by two more little cottages. The school came next (known as the National School and subsequently the Middle and now the Junior School). Next to the school playground were two more cottages. Then there was an opening with more cottages and there were more down the drive. Opposite the Queen's Head were three more cottages belonging to Hethersett Hall.

In Queen's Road, nearby the Queen's Head, was the original National School but no longer run as such at the time. It was later used as a furniture store for Mr Lemon and subsequently pulled down and a plaque was placed in the front garden of the present dwelling.

Turning left onto the main road (now Old Norwich Road) was a house and a row of Hall Cottages and at the end the harness maker, Boss Hickling. Going right past the public house you came to the blacksmith Jack Curson. The bungalow was built later. Then followed the Harvey Foundry making agricultural implements, with Cann's Lane on the corner. On the opposite corner was the Prince of Wales, and a little further along was Whitegates, owned at that time by the Boswells, wine and spirits merchants (Now Fire Service Headquarters). The King's Head came next, followed by The Priory, owned and lived in by Mr and Mrs Raikes, and then Woodhall, where Mr and Mrs Andrew and family lived. Opposite was the Old Hall, occupied by Mrs Ransom and her son. There was also a worker's cottage. Passing fields you came to Whitehall Farm (now Park Farm Hotel) and two cottages for farm workers.

Returning to New Road, then but a lane, there was nothing until you got to Eke's Farm and three or four cottages. Then there was nothing until you reached what was called Wood's Loke with a farm run by Mr and Mrs Wood (the loke is now an extension of New Road).

On to Great Melton Road and turning towards the village was The Hollies and two houses later pulled down to accommodate Glengarry Close, and then came the butcher, Edward Dann, opposite what is now Malthouse Road. Continuing on this side you came to Lynch Green, where a letter box existed for many years. On the opposite side of the road was Malthouse Farm, later taken over by Emms the Florists. There was just one house between the farm and Mill Road, where Hazel Nicholls lived with fields all around.

The Irelands moved into a council house in Lynch Green in May 1915. Proceeding down this road there was nothing on the left, but further on, on the right, were two cottages, followed by a row of cottages (since pulled down). Further down still, on the left, was Lynch Green House, then owned by the Sharman family until 1999, when Sybil Woods, Thomas Sharman's great-granddaughter, moved to Wymondham. In earlier times it had been a beer house. Lying back from this was a number of small cottages in one of which Doris Winterborn had lived. From the corner, looking down a drive, two cottages could be seen. Robert Curson had his builders and undertakers business in one, now known as Myrtle Cottage, Wiffen's Loke. On the left was a big house, later occupied by Mrs Roberts. The Thatched Cottage lay back off the road and still exists, being the only thatched dwelling in the village. Then follows the Oaks (requisitioned in the war as an officers' mess) and another dwelling. The Shrublands, followed by two little cottages (the redbrick house was built about 40 years ago). There was nothing more on the right until the White Cottage at the end. Opposite Lynch Green in Henstead Road was a row of cottages, Miller's Row. Moving right was the British School (now Church Hall) and opposite that was the Baptist Chapel, known as the Ebenezer Chapel. Next to the school was a house where the headmaster, Mr Beeby, and his family lived, and next door to that was the Greyhound. Opposite and next to the chapel was a roadway leading to some more houses. Moving along and on the right you came to the shop on the corner and opposite to that the doctor's house.

Cedar Road, passed early on the tour in Lynch Green, contained only Cedar Grange, occupied in 1922 and for several years by Judge Charles Herbert-Smith. It was gated all week, except on Sundays.

Moving south down Mill Road you pass on the right the house where a friend, Hazel Nicholls, lived, and assiduously fed and looked after the ducks.

Taking a trip down Cann's Lane, leaving Beech Cottage on the left, came the Manor House and a cottage, while down a loke there were two or three more. On the right was a grocer and a big house occupied by a market gardener. There was nothing more on the left until one reached the old A11, while on the right were the cottages of Mrs Wiseman and another. Then came a lokeway with some houses in one of which lived Mrs Bailey and her two sons, one of whom was a shoemaker. The hut in the garden was a memorial to Cyril and is engraved C.J. Bailey. Further along was another house and next to it a dwelling later pulled down.

When Ella left school there was no immediate job for her, but after a few weeks she obtained work in the Caley Factory in Norwich, to which the only transport was a bike.

* * *

For many people the village of Hethersett was a self contained backwater but for others the march of progress brought with it some problems. The Parish Magazine gave a flavour of a more hectic side of the village in September 1923 under the heading - PEACE ON THE TURNPIKE: It ran as follows -

On a certain day a few weeks back, one hundred and twenty six motor vehicles passed through Hethersett on the main road within an hour, i.e, at the rate of rather more than two a minute. What the average is per day nobody probably knows. The stream begins early in the morning and lasts late into the night, and includes vehicles of every variety, shape, weight and size. It brings with it every kind of noise and a vast amount of racket. Lorries and pantechnicons thunder through and set up a vibration which literally rattles the pictures on the walls of adjacent cottages. Motor cycles roar past with open exhausts, which make sleep an impossibility for children. Added to this is the warning note of the klaxons as they approach a bend or a crossroad at a speed which seems to hold life cheap. In Hethersett there are at least two danger spots on the turnpike at which there have occurred numbers of accidents, and yet there is no sort of warning to motorists to slow up.

Granted that all these motor-driven vehicles must pass along the road, and granted that speed is the order of the day, surely something might be done to preserve those whose houses are shaken, and nerves set on edge, and children deprived of sleep, from what has become an every day pest.

We have a flavour of what Hethersett was like in 1920 from the writings of resident Florence Eagle who, in 1924, had the following description:

"I well remember arriving in Hethersett on a sunny October day in 1924. Hethersett with a population at that time of about 1,100 seemed somewhere rather special. I decided that I must find out as much as possible about the village so that I could write in full detail to the friends I had left behind. My brother and I set off to explore the village. At that time there were two schools, three general stores, two butchers, plus two pork butchers; one of the latter was mainly a wholesaler. The Post Office was also a newsagents, tobacconist and ironmonger; at the shop opposite a variety of goods were sold including bicycles and boots and shoes. Repairs to these three items were carried out. On the site of the present supermarket stood an old army hut, where a motor and cycle repair business was carried out. Nearby stood a railway carriage which was the home and workshop of a tailor. Other businesses were builders, and an artesian-well engineer, a blacksmith and there were four public houses. The doctor's surgery was at Hethersett House.

I remember being impressed by the number of people in the church choir, including several middle-aged men. At that time the Methodist Church had a good male voice choir.

My visits to Norwich had been few and far between. I was pleased to find that buses ran to Norwich from Hethersett even though they were from the main road. There were no petrol pumps in the village. My father bought a motor vehicle before moving to Hethersett and he purchased his petrol in cans from the Post Office.

In 1924, quite a number of people were employed in the village. Apart from the businesses already mentioned there were farms, market gardens, an agricultural engineer, two coal merchants, a corn merchant, a saddler and at least 17 houses employed gardeners and indoor staff, some employed chauffeurs.

Quite a lot of laundry work was carried out in the village for people outside Hethersett. I think it was mainly for residents in the Newmarket Road, Norwich area. Hethersett had neither gas nor electricity. Gas came first in approximately 1925; when electricity came about a year later several people had their gas fittings removed and changed to electricity.

The roads were quite rough in those days, however, as it was before the car age many people enjoyed their Sunday afternoon walk; a popular round was Great Melton Road, New Road, the Main Road and Queen's Road, at that time there were no houses along New Road after turning left at Mill Road corner towards the main road.

Quite a number of houses in Lynch Green, Great Melton Road and some in Queen's Road were way back with a meadow or long garden in front of the house; several of these frontages have now been built on.

Ella Barnes (nee Ireland) was born in Hethersett in 1911 and wrote about a walk around Hethersett in the 1920s when there was plenty of open space and fields:

There was no electricity, gas or piped water. Water was obtained from wells and pumps and the roads were untarred:

"Walking down Great Melton Road from Lynch Green, apart from dwellings occupied by Mr and Mrs Mapes and one by Mr Levine, there was no other development on the right nearly down to the junction with Henstead Road. On the left were the dovecoats, next to two little cottages .... Then there were two small cottages on the other side of the road. Further along was the chapel and next it it a grocer's shop run by a Mr and Mrs Kent. In Oak Square was a bakery run by two Mr Smiths, while next was a butchers, William Curson. Then came two more little houses. Mr and Mrs Pike lived in one, and he was a gents' hairdresser (called a barber), while in the other lived PC Burton and his family. There was nothing further on this side until the Post Office on the corner (now the McMillan Charity Shop) run by Miss Buckingham and her son. Almost opposite in Great Melton Road was a long driveway to a house and alongside was the old bicycle shop which also sold paint, wallpaper and a few clothes, and this was run for years by the Childs' family until it is thought the lease ran out. The big house next to this and down another driveway included a pork butcher run by Ernest Smith.

On the right, further down the road, was a grocer's shop run by Mr and Mrs Sharman. Just past the grocers was a house standing back from the road. There was nothing more until Cann's Lane. On the other side of the road there were no buildings until you reached Beech Grove Farmhouse. On the corner of Cann's Lane was Beech Cottage. There was nothing on either side until you reached a row of cottages next to the then Village Hall and what is now Hethersett Social Club. Then followed a grocer's shop followed by two more little cottages. The school came next (known as the National School and subsequently the Middle and now the Junior School). Next to the school playground were two more cottages. Then there was an opening with more cottages and there were more down the drive. Opposite the Queen's Head were three more cottages belonging to Hethersett Hall.

In Queen's Road, nearby the Queen's Head, was the original National School but no longer run as such at the time. It was later used as a furniture store for Mr Lemon and subsequently pulled down and a plaque was placed in the front garden of the present dwelling.

Turning left onto the main road (now Old Norwich Road) was a house and a row of Hall Cottages and at the end the harness maker, Boss Hickling. Going right past the public house you came to the blacksmith Jack Curson. The bungalow was built later. Then followed the Harvey Foundry making agricultural implements, with Cann's Lane on the corner. On the opposite corner was the Prince of Wales, and a little further along was Whitegates, owned at that time by the Boswells, wine and spirits merchants (Now Fire Service Headquarters). The King's Head came next, followed by The Priory, owned and lived in by Mr and Mrs Raikes, and then Woodhall, where Mr and Mrs Andrew and family lived. Opposite was the Old Hall, occupied by Mrs Ransom and her son. There was also a worker's cottage. Passing fields you came to Whitehall Farm (now Park Farm Hotel) and two cottages for farm workers.

Returning to New Road, then but a lane, there was nothing until you got to Eke's Farm and three or four cottages. Then there was nothing until you reached what was called Wood's Loke with a farm run by Mr and Mrs Wood (the loke is now an extension of New Road).

On to Great Melton Road and turning towards the village was The Hollies and two houses later pulled down to accommodate Glengarry Close, and then came the butcher, Edward Dann, opposite what is now Malthouse Road. Continuing on this side you came to Lynch Green, where a letter box existed for many years. On the opposite side of the road was Malthouse Farm, later taken over by Emms the Florists. There was just one house between the farm and Mill Road, where Hazel Nicholls lived with fields all around.

The Irelands moved into a council house in Lynch Green in May 1915. Proceeding down this road there was nothing on the left, but further on, on the right, were two cottages, followed by a row of cottages (since pulled down). Further down still, on the left, was Lynch Green House, then owned by the Sharman family until 1999, when Sybil Woods, Thomas Sharman's great-granddaughter, moved to Wymondham. In earlier times it had been a beer house. Lying back from this was a number of small cottages in one of which Doris Winterborn had lived. From the corner, looking down a drive, two cottages could be seen. Robert Curson had his builders and undertakers business in one, now known as Myrtle Cottage, Wiffen's Loke. On the left was a big house, later occupied by Mrs Roberts. The Thatched Cottage lay back off the road and still exists, being the only thatched dwelling in the village. Then follows the Oaks (requisitioned in the war as an officers' mess) and another dwelling. The Shrublands, followed by two little cottages (the redbrick house was built about 40 years ago). There was nothing more on the right until the White Cottage at the end. Opposite Lynch Green in Henstead Road was a row of cottages, Miller's Row. Moving right was the British School (now Church Hall) and opposite that was the Baptist Chapel, known as the Ebenezer Chapel. Next to the school was a house where the headmaster, Mr Beeby, and his family lived, and next door to that was the Greyhound. Opposite and next to the chapel was a roadway leading to some more houses. Moving along and on the right you came to the shop on the corner and opposite to that the doctor's house.

Cedar Road, passed early on the tour in Lynch Green, contained only Cedar Grange, occupied in 1922 and for several years by Judge Charles Herbert-Smith. It was gated all week, except on Sundays.

Moving south down Mill Road you pass on the right the house where a friend, Hazel Nicholls, lived, and assiduously fed and looked after the ducks.

Taking a trip down Cann's Lane, leaving Beech Cottage on the left, came the Manor House and a cottage, while down a loke there were two or three more. On the right was a grocer and a big house occupied by a market gardener. There was nothing more on the left until one reached the old A11, while on the right were the cottages of Mrs Wiseman and another. Then came a lokeway with some houses in one of which lived Mrs Bailey and her two sons, one of whom was a shoemaker. The hut in the garden was a memorial to Cyril and is engraved C.J. Bailey. Further along was another house and next to it a dwelling later pulled down.

When Ella left school there was no immediate job for her, but after a few weeks she obtained work in the Caley Factory in Norwich, to which the only transport was a bike.

* * *

For many people the village of Hethersett was a self contained backwater but for others the march of progress brought with it some problems. The Parish Magazine gave a flavour of a more hectic side of the village in September 1923 under the heading - PEACE ON THE TURNPIKE: It ran as follows -

On a certain day a few weeks back, one hundred and twenty six motor vehicles passed through Hethersett on the main road within an hour, i.e, at the rate of rather more than two a minute. What the average is per day nobody probably knows. The stream begins early in the morning and lasts late into the night, and includes vehicles of every variety, shape, weight and size. It brings with it every kind of noise and a vast amount of racket. Lorries and pantechnicons thunder through and set up a vibration which literally rattles the pictures on the walls of adjacent cottages. Motor cycles roar past with open exhausts, which make sleep an impossibility for children. Added to this is the warning note of the klaxons as they approach a bend or a crossroad at a speed which seems to hold life cheap. In Hethersett there are at least two danger spots on the turnpike at which there have occurred numbers of accidents, and yet there is no sort of warning to motorists to slow up.

Granted that all these motor-driven vehicles must pass along the road, and granted that speed is the order of the day, surely something might be done to preserve those whose houses are shaken, and nerves set on edge, and children deprived of sleep, from what has become an every day pest.